2022 was marked by a regime change, during which a long-exalted strategy for constructing portfolios broke down.

In the first nine months of 2022, roughly $36 trillion was lost across the Bloomberg Global Aggregate Bond Index and the MSCI All-Country World Stocks Index combined. As a result of this drop in value across both markets, the traditional portfolio comprising 60% public equities and 40% bonds—a.k.a. the 60/40 portfolio—experienced one of its worst years on record, falling 16.9%, the lowest return since the Global Financial Crisis.

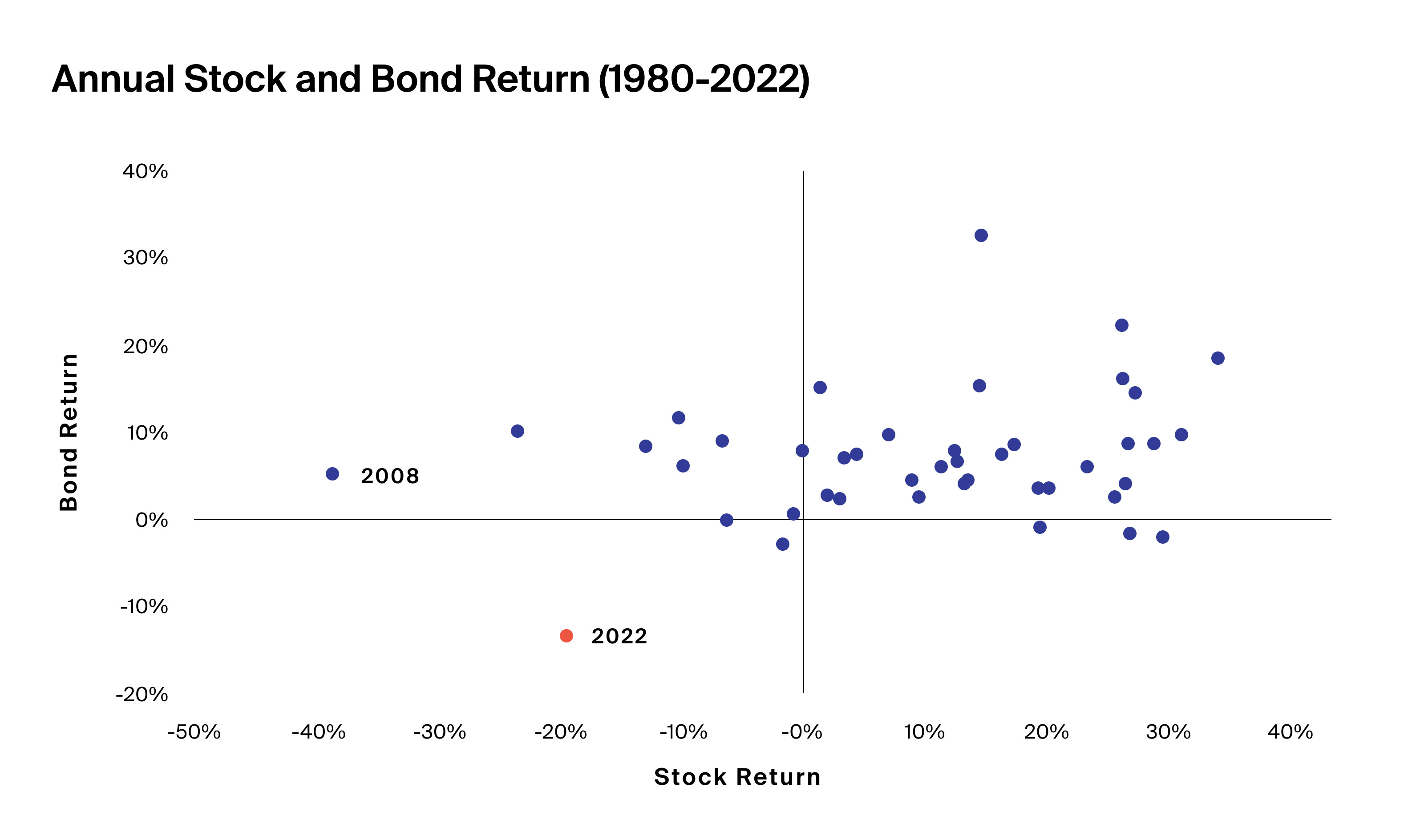

In 2008, the last time that the 60/40 performed as badly, equities fell 38.5% while bonds still returned 5.2%,1 maintaining a hedge to the downside experienced by equities. In 2022, however, equities and bonds fell in unison (Exhibit 1), causing investors to call into question the dependability of the long-standing investment strategy.

Source: Bloomberg, Stock Return represented by the S&P 500 Index, Bond Return represented by the Bloomberg US Aggregate Total Return Value Unhedged USD Index, as of 12/2022.

In 2022, equities and bonds fell in unison, causing investors to call into question the dependability of the long-standing investment strategy.

In this piece, we explore potential lessons about the traditional 60/40 portfolio from this past year. We also discuss how expanded access to alternative strategies may support independent financial advisors as they revisit their strategic asset allocations.

Does the 60/40 Portfolio Still Work?

The 60/40 portfolio investment strategy was developed by Harry Markowitz in 19522 and was underpinned by the Modern Portfolio Theory.3 Markowitz proposed a way that investors could construct portfolios to seek to maximize expected returns based on a given level of market risk. They could do so, he suggested, by diversifying across assets with uncorrelated returns.4

For much of the strategy’s history, therefore, the efficacy of the 60/40 portfolio has been determined by the low correlation between its two broad components: public equities and bonds. According to the theory, if that low or negative correlation holds, an equity downturn would be offset by the bond portion of the portfolio and vice versa.

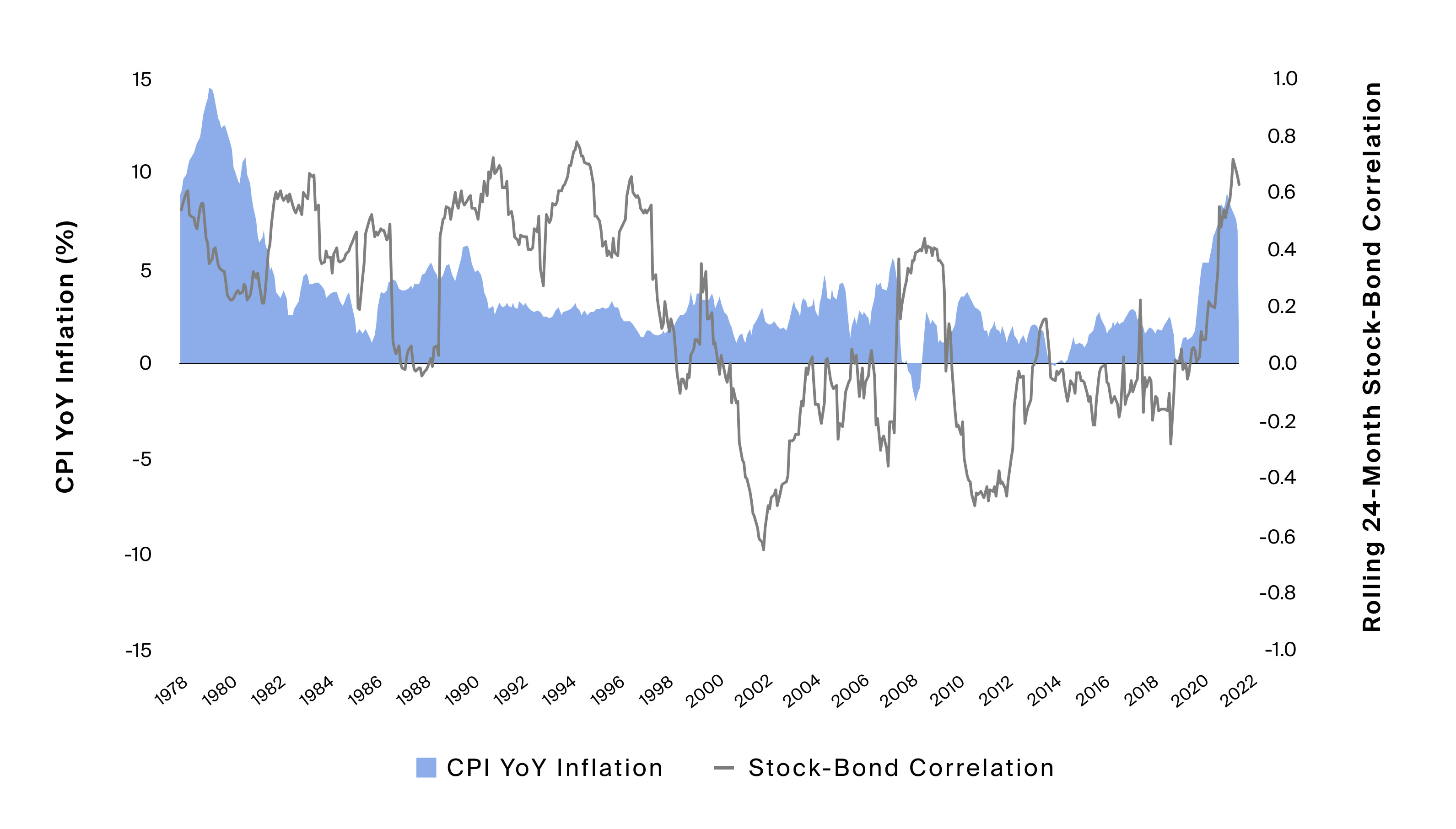

In 2022, amid high inflation and rising rates, we saw a spike in the 24-month stock-to-bond correlation, which ended the year at 0.63, after previously reaching a 27-year peak at 0.72 in September (Exhibit 2). In short, the very keystone of the 60/40 portfolio—the low correlation of stocks to bonds—did not hold.

Source: Bloomberg, CPI YoY Inflation represented by US CPI Urban Consumers YoY NSA, Stock-Bond Correlation represented by a 60% and 40% weighted allocation to the S&P 500 Index and the Bloomberg US Aggregate Total Return Value Unhedged USD Index, as of 12/2022.

In 2022, amid high inflation and rising rates, we saw a spike in the 24-month stock-to-bond correlation, which ended the year at 0.63, after previously reaching a 27-year peak at 0.72 in September.

Since September, adherents to the 60/40 have rejected the supposed death knell of the strategy, arguing that a single year’s performance is not enough to discount its long-term merits in a portfolio.5 Both equity and bond prices may indeed see a revival.

For one, equities may now offer a more attractive entry point from a valuation perspective. In addition, as the Fed raises its benchmark rate to combat inflation, bonds may provide a real yield over 1% for the first time since August 2009.6 They may also offer more meaningful nominal yields, providing a greater cushion against potential price decreases. Lastly, if one takes the view that inflation has indeed peaked, the trajectory of the economy may also appear more certain, presenting a potential opportunity for equities to recover and bond prices to rise.

Given the continued uncertainty around the ultimate path of inflation, interest rates and economic growth, we believe that a return to a low correlation between equity and bond returns, which would theoretically bolster the 60/40 portfolio’s long-term balance, remains uncertain. Markowitz’s theory depends on differentiated returns across market environments; thus, diversifying beyond stocks and bonds may offer even more portfolio resiliency than the traditional 60/40 could.

Pursuing an Alternative Efficient Frontier

In the eras in which the 60/40 portfolio was invented and popularized, most investors lacked access to anything but stocks and bonds to diversify their portfolios.7 Now, many more have the potential to incorporate alternative investments.

According to financial advisors surveyed in a recent CAIS-Mercer survey,8 many may be looking to access this expanded toolset. About 88% plan to increase their allocation to alternatives over the next two years. More than half estimate that their allocation to alternatives will comprise more than 15% of their overall allocations.

Many asset managers surveyed also expressed their intention to provide greater access, with most respondents (63%) in the asset manager group readying new products in the coming years. Nearly half (46%) said that they plan to roll out new structures, such as interval funds or 40 Act liquid alternative funds.

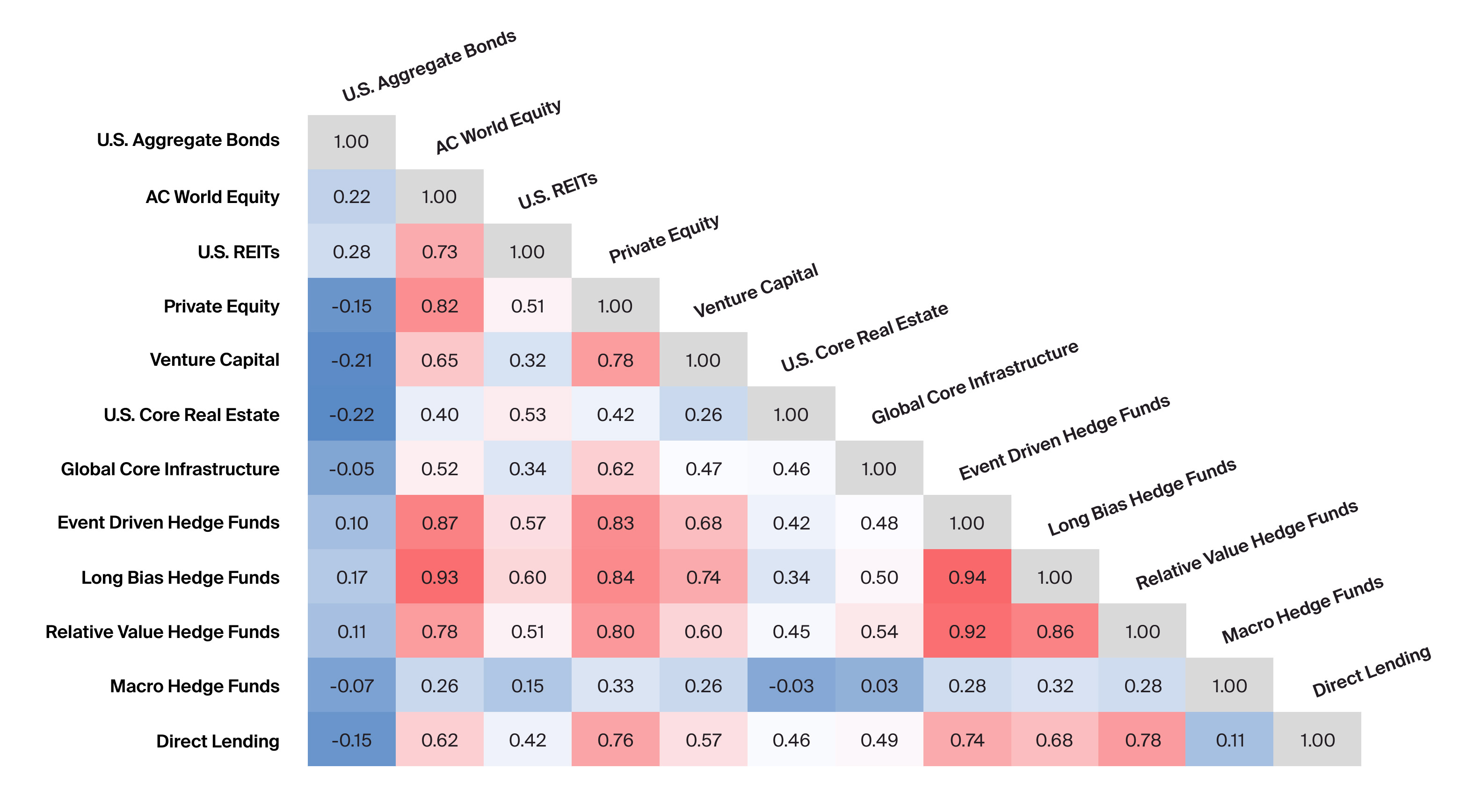

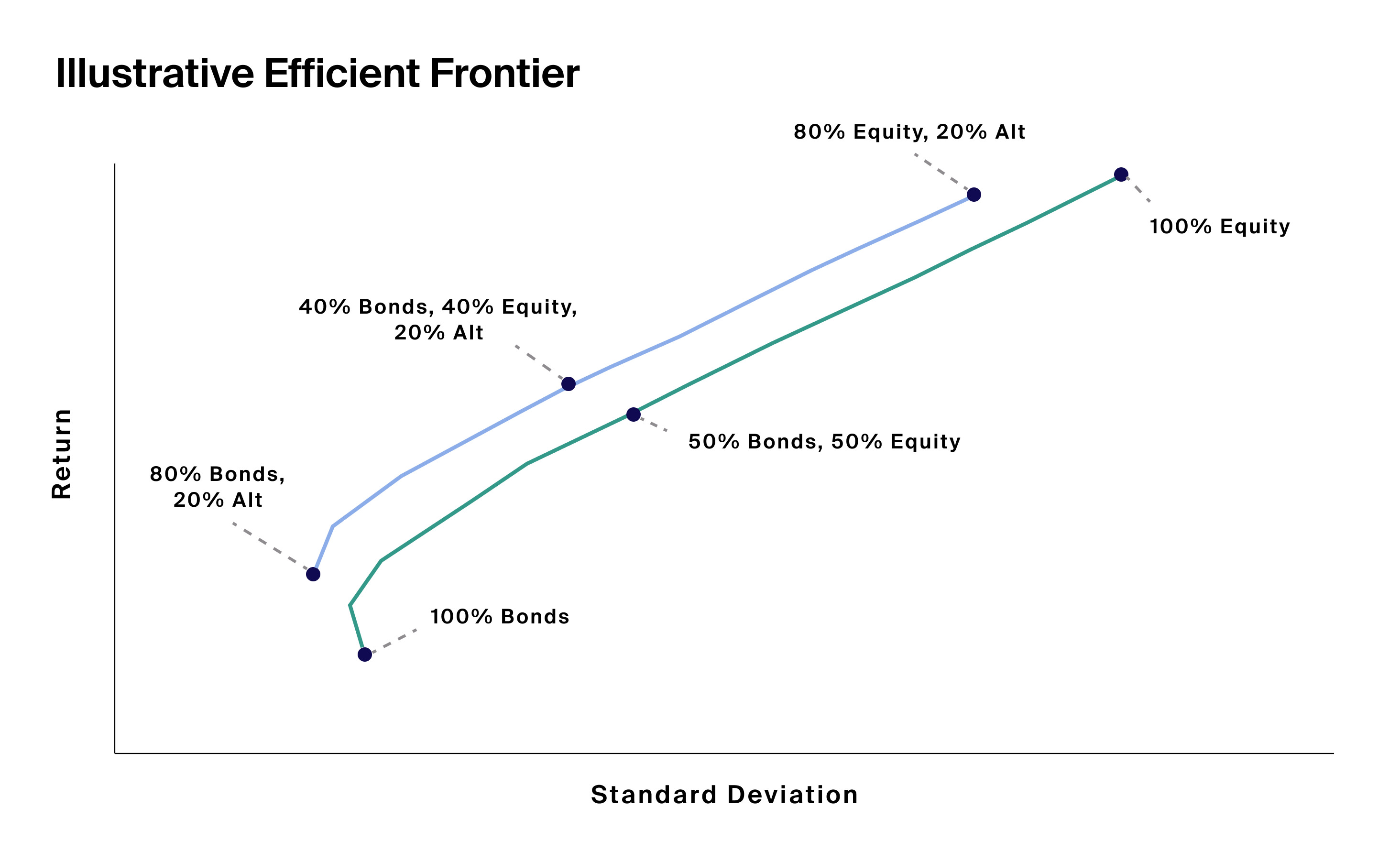

With greater access, advisors might reconsider their strategic asset allocation using the same mathematical principles that made the 60/40 so successful for decades. Namely, they could aim to improve a portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns through the inclusion of asset classes and strategies that generate non-correlated returns to equities, bonds or both (Exhibit 3).

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management; as of September 30, 2022.

With greater access, advisors might reconsider their strategic asset allocation using the same mathematical principles that made the 60/40 so successful for decades. Namely, they could aim to improve a portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns through the inclusion of asset classes and strategies that generate non-correlated returns to equities, bonds or both.

Modern Portfolio Theory supports the notion that an investor should be willing to accept a proportional amount of risk in exchange for a greater expected return. Greater risk-adjusted return, through the minimization of idiosyncratic risk, may be achieved through diversification—a function of correlation.9 The portfolios that optimize ideal levels of risk and return are said to exist on what Markowitz coined, the efficient frontier.

Based on Markowitz’s original principles, adding alternatives with low correlations to public equities or traditional fixed income could potentially shift this frontier up and to the left, increasing returns, while reducing risk (Exhibit 4). Of course, like with traditional assets, these potential outcomes depend on the particular assets or strategies an investor selects for a portfolio, and each comes with its own significant risks. A portfolio incorporating alternatives would generally be more complex and illiquid than one that includes traditional assets alone.

Footnotes

This graphic is provided for illustrative purposes only.

Based on Markowitz’s original principles, adding alternatives with low correlations to public equities or traditional fixed income could potentially shift this frontier up and to the left, increasing returns, while reducing risk.

Alternative Return Streams and Strategic Considerations

Fundamentally, alternative investments tend to pursue the same basic investment objectives within a portfolio as their traditional counterparts: enhancing returns, diversifying risks and supplementing income. Yet, in part because of the greater degree of risk many are willing to assume, alternative investment strategies can employ tactics and access segments of the financial markets that traditional strategies cannot. Therefore, they may offer returns that are differentiated—or less correlated—to stocks and bonds across market cycles and varying macroeconomic conditions.

In this section, we look at three common functions of certain alternative asset classes that may enable their investors to pursue similar investment outcomes differently than those who invest exclusively in a traditional 60/40 portfolio.

Addressing Market Volatility and Dispersion

Periods of heightened market volatility, much like what we have experienced in the past year, may result in a large dispersion of returns across and within asset classes. Such dispersion generally poses both systematic risk and opportunity for investors. While dispersion alone may present directional risk to a long-only portfolio, for certain alternative investment strategies, such as long/short hedge funds, the same dispersion may be an opportunity to generate alternative sources of return.

Structured products that aim to provide downside protection may offer investors a similar opportunity to minimize and capitalize upon volatility and dispersion. Returns on these products are typically not the same as investing directly in a particular asset and have different market risk characteristics when compared to traditional investments. These products can take many different forms, including notes with dual directional features, similar to the return streams in long/short hedge funds, which are designed to provide investors with the potential to capture the absolute performance of an underlying asset or benchmark, down to a predetermined level.

Hedge funds and other strategies that employ multi-directional tactical allocations may present non-correlated sources of return, despite trading in many of the same securities that a traditional 60/40 portfolio might hold. Therefore, traditional allocations combined with diversifying long/short strategies may have the potential to offset risk in a portfolio and increase risk-adjusted return across market environments.

Capturing Private Market Growth

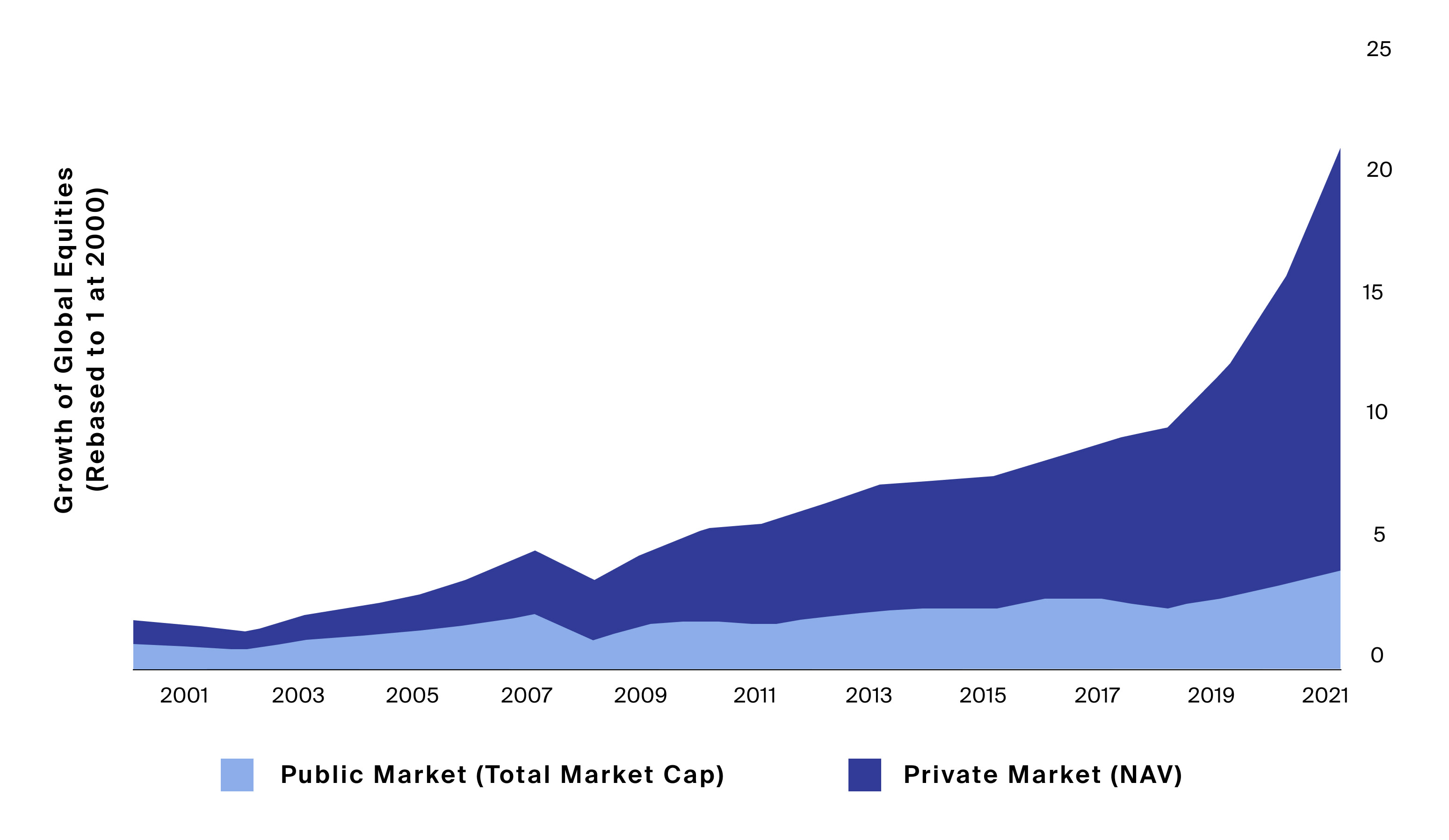

According to Preqin, private market growth is expected to continue, with AUM in private equity and private debt expected to double to $18.3 trillion by the end of 2027.10 Global private equity net asset value, or NAV, has grown nearly 17.6x since 2000, compared to the total market capitalization of the public equity market which has grown 4.1x in the same time (Exhibit 5). Investors focused solely on traditional long-only equity strategies may be missing out on this rapidly expanding universe of companies, an ever-increasing proportion of the total equity universe.

Source: Preqin, Net Asset Value = Assets Under Management – Dry Powder, as of 12/2021. World Federation of Exchanges, Total Market Cap represented by the total market cap of companies globally, as of 12/2021.

Global private equity net asset value, or NAV, has grown nearly 17.6x since 2000, compared to the total market capitalization of the public equity market which has grown 4.1x in the same time.

What’s more, a growing trend of companies staying private longer has expanded the opportunity set for private market investors. Companies are staying private longer due to a confluence of reasons. They may wish to avoid the regulatory and earnings scrutiny that comes with public listings. They also now have greater access to private capital to fuel their growth—through venture funding, a broadening secondary market and emerging structures like continuation funds.11

While staying private longer may have its benefits at the company level, early company growth is nearly inaccessible now on public exchanges. To quantify, in 1980, the median market value of a company at its IPO was $105 million, adjusted for inflation. In 2021, the median market value was $1.33 billion.12 At these valuations, by the time many companies reach the public market, their growth phases have been squeezed and they are not reaching the public market until they are nearly 10 times larger than they were decades ago.

Therefore, if you’re an advisor targeting growth, investing solely in public stocks may mean missing out on the earlier and often more accretive growth phases in a company’s lifecycle and being limited to the ever-shrinking proportion of the total equity landscape.

Of course, when considering new asset classes, especially ones as sophisticated and complex as private equity, an advisor should familiarize themselves with relevant risks. These could potentially include illiquidity, lack of transparency around the underlying portfolio, the J-curve, concentration risks and others specific to the fund manager or strategy.

Seeking to Generate Alternative Sources of Income

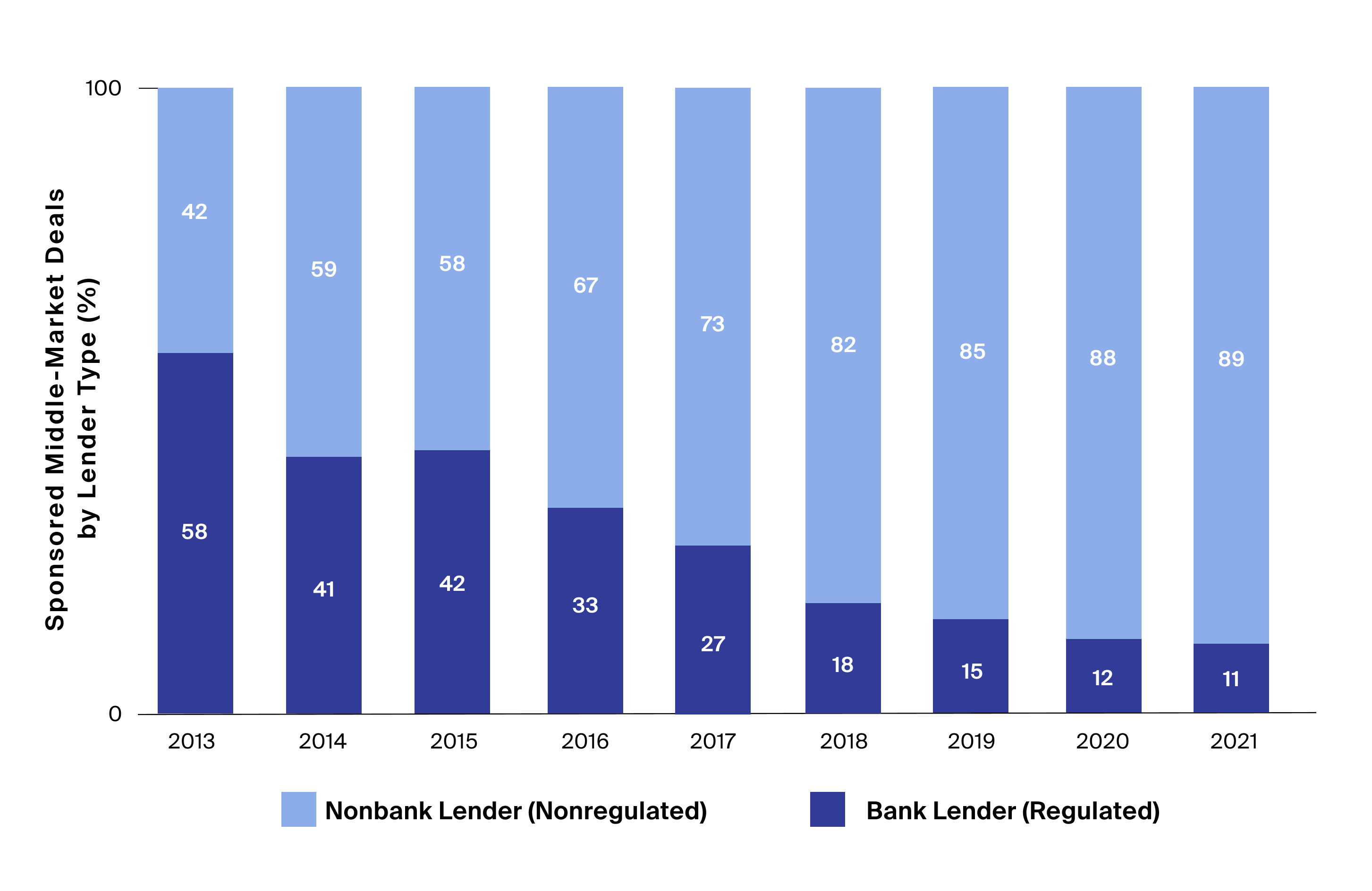

As private equity growth outpaces public equity growth, increasingly those private companies, and indeed some public companies recently,13 are fueling their operations and expansion through private debt (Exhibit 6). The private debt market has tripled in size since 2008.14

Direct lending—private debt funds that make floating-rate loans to private companies without the use of financial intermediaries such as banks—has seen outsized growth in recent years due to the sidelining of traditional lenders. In fact, bank lenders as of 2021 made up just 11% of sponsored middle-market financing (Exhibit 5). In addition, tightening liquidity in the current environment has appeared to enable improved lending terms, higher absolute yields and more attractive counterparties for direct lenders.15

Source: Refinitiv (deals submitted to private database).

Private debt funds that make floating-rate loans to private companies without the use of financial intermediaries such as banks—has seen outsized growth in recent years due to the sidelining of traditional lenders. In fact, bank lenders as of 2021 made up just 11% of sponsored middle-market financing.

The private debt market is highly diverse in what it can offer from a risk-return standpoint.16 Strategies like distressed and special situations strategies may offer countercyclical characteristics. Direct lending tends to be more expansionary17 and may have the ability to generate higher returns than traditional strategies like broadly syndicated loans, with potentially less risk.

Structured products, particularly yield notes, may also play a role in diversifying an income-seeking portfolio. Depending on how the notes are structured and the underliers used, they may provide a yield that’s uncorrelated to traditional fixed income. The returns on these products are not directly tied to the performance of a particular asset or index. Rather, the yield can be fixed and periodic or contingent on an underlier. As a result, yield notes can be a useful tool for investors who are seeking to diversify their portfolio. However, like all structured notes, such yield notes carry additional risks, specifically around illiquidity, complexity, callability of the note and the credit of the issuer.

Same Modern Portfolio Theory: New Components and Additional Risks

The hedging capability of the 60/40 portfolio deteriorated amid high inflation and unprecedented rate hikes in 2022. This collapse might serve as a wake-up call for those with traditional strategic asset allocations to reevaluate their portfolios and consider whether their allocations are diversified enough to be resilient in uncertain markets that may lie ahead.

Given their increasing access to alternative investments, advisors might consider incorporating additional sources of non-correlated return as they seek to increase the resiliency and risk-adjusted returns of their portfolios. However, alternatives come with additional risks, particularly for strategies that employ leverage, such as hedge funds. Because of their sophisticated trading practices, many of these alternative strategies may run the risk of losing some or all capital invested.

Investors in certain private funds discussed above, such as private equity, real estate, or infrastructure, may face concentration risks and the J-curve typical in drawdown funds. As such, investors may aim to diversify across managers, geographies, vintage years, strategy types and property sectors. Many private investments also tend to be relatively illiquid, and advisors should understand their clients’ liquidity needs before investing across strategies.