Learn about hedge funds and the variety of strategies

What Are Hedge Funds?

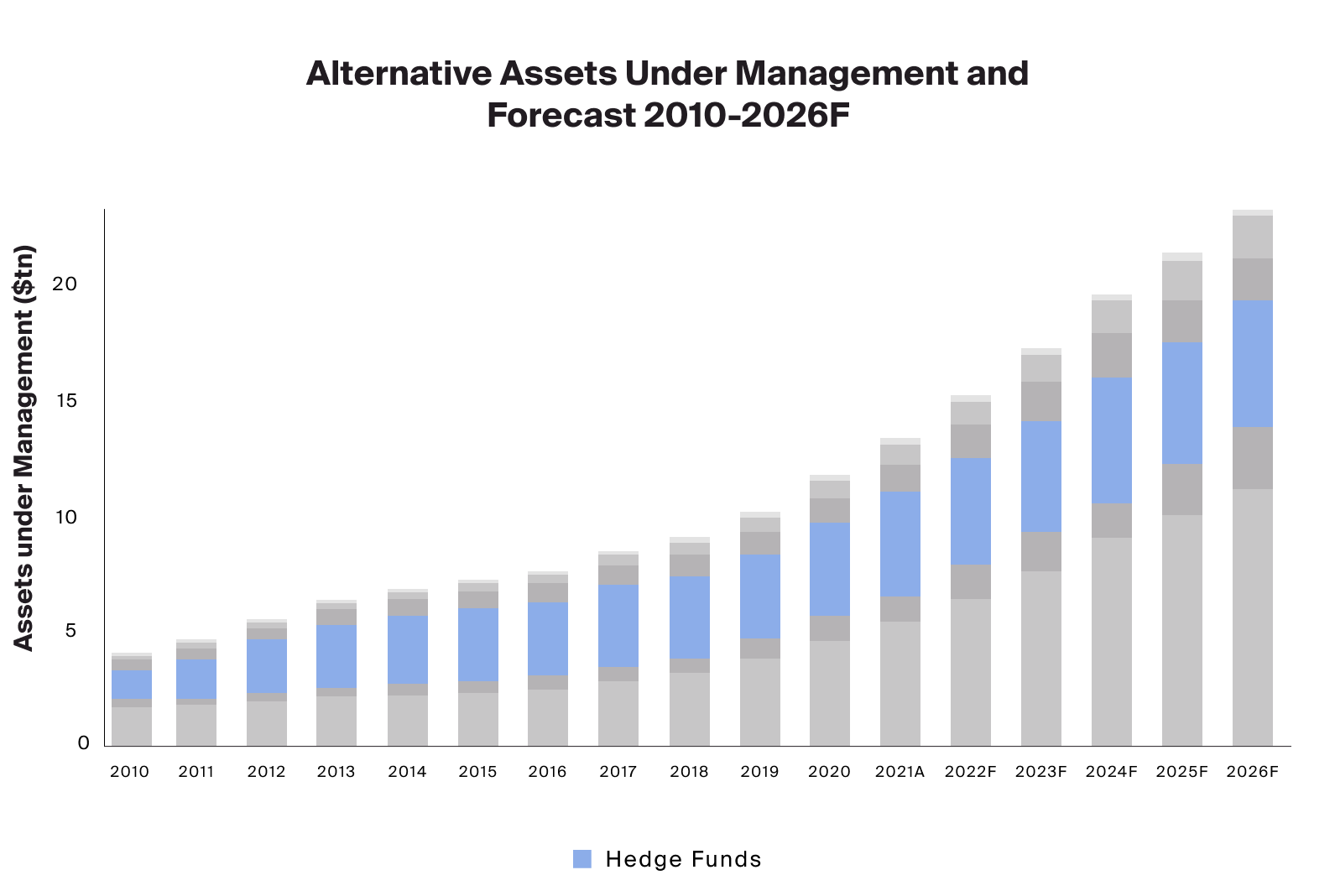

Hedge funds are commonly defined as private, actively managed, pooled investment vehicles. Assets under management (AUM) for hedge funds reached $4.3 trillion in 2021 and could grow to over $5 trillion by 2026, making this alternative asset class the second largest behind private equity by AUM (Exhibit 1).

Source: Preqin Pro, as of Q3 2021, 2021 figure is annualized based on data to March, 2022-2026 are Preqin's forecast figures.

Hedge funds are commonly defined as private, actively managed, pooled investment vehicles. Assets under management (AUM) for hedge funds reached $4.3 trillion in 2021 and could grow to over $5 trillion by 2026, making this alternative asset class the second largest behind private equity by AUM

Put simply, compared to traditional asset classes, such as equities and bonds, and traditional vehicles, such as mutual funds and ETFs, hedge funds may offer potentially higher returns for investors willing to take a higher level of risk.

As private investments, hedge funds are generally subject to less regulation than many traditional investments, such as mutual funds, potentially giving them more flexibility in terms of the assets they can invest in, their investment style and the management of the fund. This flexibility can be important because the goal for many hedge funds is to earn positive risk-adjusted performance in all market conditions.

Guidelines for hedge funds tend to have fewer restrictions, often allowing them to employ strategies that are not typically used in mutual funds that can potentially provide additional sources of return. Some of these strategies include dynamic trading strategies that seek to profit from small moves in a market even intra-day; investing in a wide range of assets, including less-liquid securities; using financial instruments, such as options and derivatives; taking short positions in stocks with the goal of profiting from decreases in prices; and using leverage in an effort to enhance returns.

Some of these drivers of potentially higher returns may expose funds to additional risks: frequent trading can incur high transaction costs that chip away returns; less-liquid assets can be harder to sell during times of market stress; in contrast to long positions, where the downside is limited to a stock’s decline in value to zero, short positions have an unlimited downside because a stock can trade infinitely higher.

Some investors may be concerned that the returns from traditional asset classes in recent years may not be easily repeated in the coming years, particularly as inflation and interest rates rise. As a result, they may be looking to diversify their portfolios and seeking to understand how hedge funds fit into an asset allocation strategy.

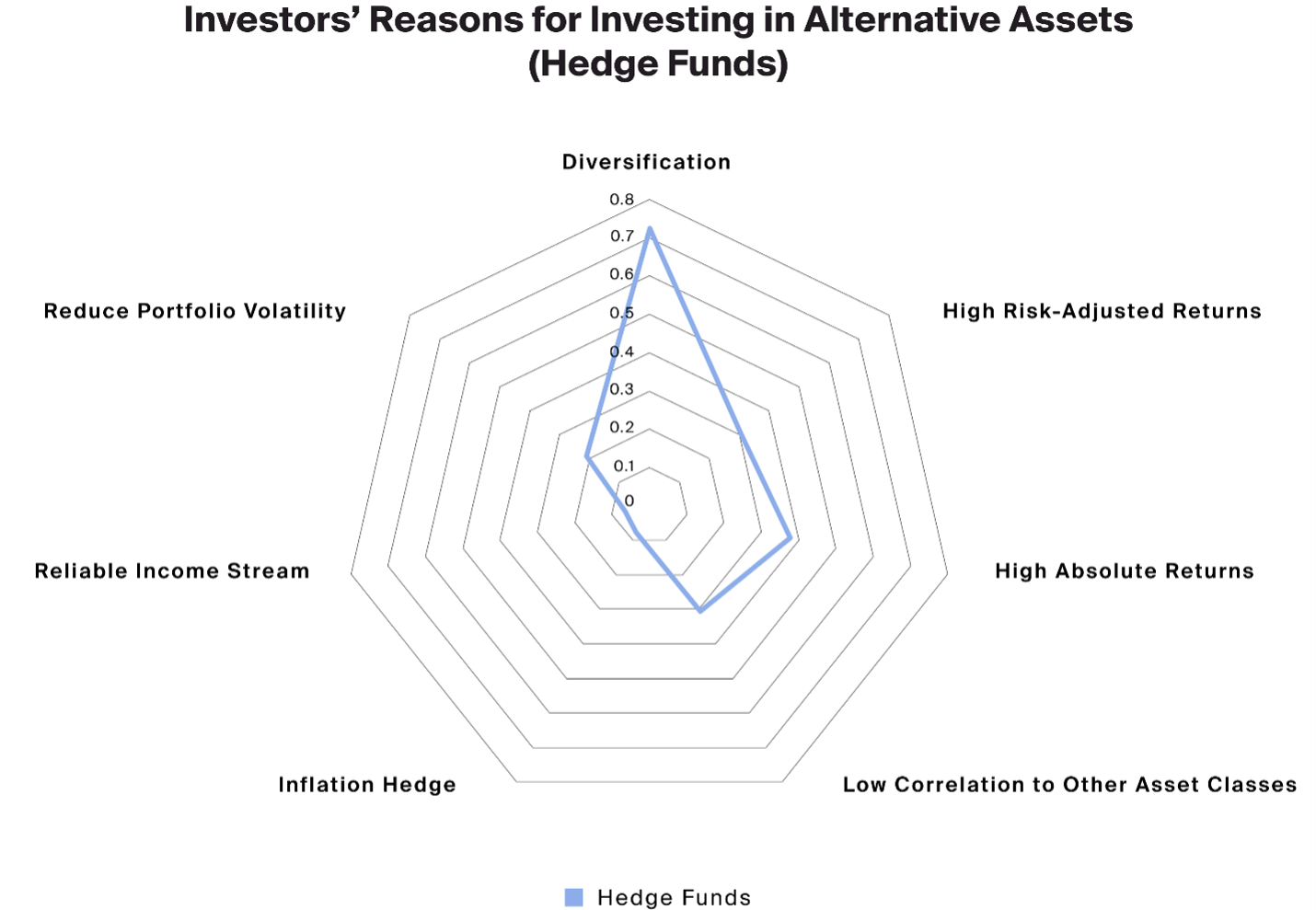

While one reason to consider hedge funds is the potential to generate higher returns than traditional assets classes, many hedge funds are managed by “hedging” or offsetting risks, making returns less correlated to the market environment, which can potentially improve the risk-adjusted returns of a portfolio (Exhibit 2). In fact, some analyses show that adding hedge funds to a basket of traditional assets may reduce portfolio risk while improving returns.1 The sources of return for many hedge fund strategies may also be different and more diverse than traditional equity and bond allocations, potentially resulting in less correlation to these asset classes.

Source: Preqin Investor Survey, November 2021.

While one reason to consider hedge funds is the potential to generate higher returns than traditional assets classes, many hedge funds are managed by “hedging” or offsetting risks, making returns less correlated to the market environment, which can potentially improve the risk-adjusted returns of a portfolio.

What Are Some Common Types of Hedge Funds?

While each hedge fund will have its unique investment strategy, there are some broad categories, each with different risk and return characteristics.

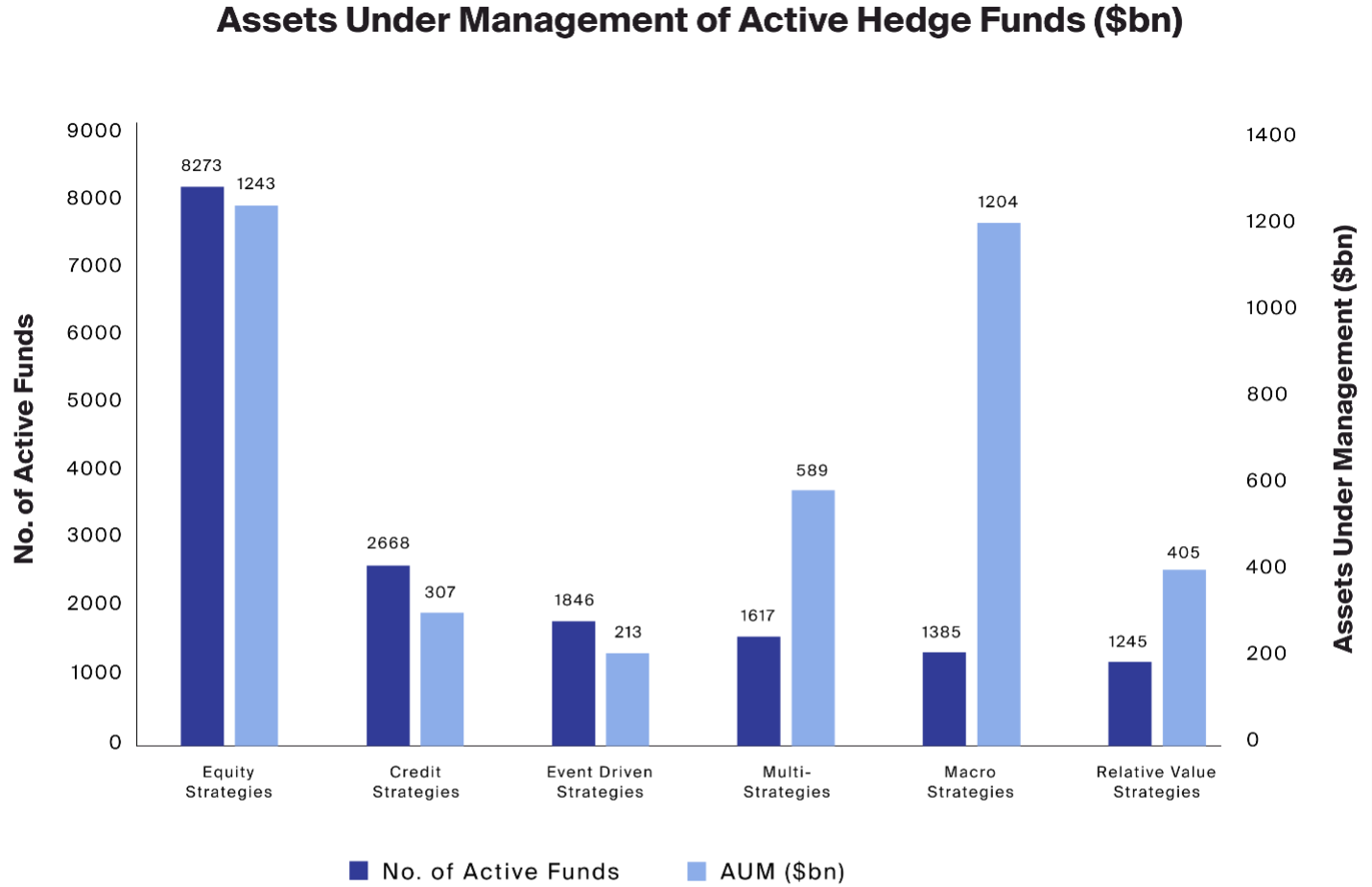

Equity hedge is the most common strategy used by managers (Exhibit 3). It often combines both long and short positions in stocks with the objective of generating returns on both, while also seeking to minimize exposure to the market.

Credit strategies generally focus on arbitrage opportunities, such as between junior and senior debt of the same issuer, between securities with similar credit profiles from different issuers, or within more complex structures.

Relative value strategies typically seek to generate returns by exploiting pricing inefficiencies between related financial instruments such as stocks or bonds.

Event-driven strategies tend to focus on mispriced securities that may have catalysts, such as mergers, acquisitions, reorganizations, bankruptcies, or other unique corporate actions, that could help realize their true value.

Macro hedge funds broadly aim to profit from market swings caused by political or economic events; they seek to maximize returns in periods of high market volatility and low liquidity.

Source: Preqin Pro, as of October 2021.

The most common strategies used by Hedge Fund managers.

There are also several common hedge fund structures:

Single-Strategy hedge funds invest using one investment strategy.

Multi-Strategy hedge funds invest in several different strategies within a single fund.

Funds of Hedge Funds (FoHF) generally invest in a collection of different hedge funds, typically looking to diversify risk from any single strategy or manager. These funds often include an additional layer of fees.

Considerations When Investing in Hedge Funds

Manager Selection/Access: Manager skill can be important to a hedge fund’s success, meaning investors should carefully evaluate managers. Hedge funds typically require high minimum investments and are generally only available to accredited investors or qualified purchasers.

Performance Measurement: Generally, hedge funds are evaluated using an absolute return standard, such as a risk-free return level plus a spread, and therefore, independent of how the market or benchmarks are performing.

Fees: Fee structures vary greatly across the industry, but hedge fund fees are generally higher than those for traditional assets and tend to include an additional performance component. A common fee structure is “2 and 20,” which is a 2% management fee applied each year to the total assets under management and a 20% incentive fee (or performance fee) charged on the profits earned over a hurdle rate.

Liquidity: Investments in hedge funds are generally much less liquid than investment vehicles associated with traditional asset classes, such as mutual funds and ETFs, because they do not trade on an exchange and are not open-ended funds with daily liquidity. Furthermore, in order to properly execute their strategies, many hedge funds have lockup periods of about one to two years when investors are unable to withdraw or sell back investments. However, hedge funds may be more liquid than many other alternative investments due to more liquid underlying assets and shorter lockups.

Regulation: Disclosures for hedge funds are often not mandated, reviewed or approved by regulatory bodies. As a result, investors need to conduct independent analysis and evaluation of a hedge fund’s underlying investments or strategies to compensate for the lack of transparency. This can differ significantly from a mutual fund, which is a highly regulated investment vehicle offering relatively transparent, frequent, and standardized reporting.

Leverage: This form of borrowing is used by many hedge funds in an effort to increase the power of every dollar contributed to the fund by investors. A variety of financial instruments, such as options, swaps and futures, can add leverage to a portfolio. Investors should understand that these instruments come with costs and increase the risk of the portfolio because leverage can also amplify losses.

Hedge funds have been growing in recent years and this trend could continue as hedge funds become accepted by and accessible to a wider audience.