What Is a Buyout Fund?

A buyout fund is a type of private equity (PE) fund that typically seeks to gain controlling or majority (>50%) ownership of a company, with the goal of creating value by improving the operations of the company.1 The PE firm overseeing the fund later seeks to sell or take these companies public at higher valuations. Institutional investors (including pension funds) tend to incorporate PE buyout strategies as a part of their efforts to seek higher absolute or risk-adjusted returns.2

Buyouts are the largest of the three main categories of PE strategies—along with venture capital and growth equity—and the strategy commonly associated with PE investing.3

What Is the Typical Life Cycle of a Buyout Fund?

Buyout funds with a finite-life, drawdown structure tend to have a seven to 10-year lifecycle, with distinct phases: fundraising, investment, and harvest.4 (Note that these phases may be broken out or named differently across the industry, yet most funds follow a similar sequence. LPs are usually expected to commit capital to a blind pool during the fundraising phase, which means they won’t know the composition of the fund before they invest.

More recently, some asset managers have been offering buyout strategies via semi-liquid interval fund structures, which may offer immediate exposure to a portfolio of assets along with limited periodic redemptions.

What Characteristics Are Unique to Buyout Strategies?

Compared to venture capital and growth equity funds, buyout funds tend to purchase a controlling interest in more mature companies that are further along in their lifecycle.5 These target companies tend to have more established business models and predictable cash flows than those that attract venture or growth equity capital. In a buyout, the underlying company may be publicly listed or privately held at the time of purchase. Often, the company goes up for sale to allow existing owners an exit strategy to cash out their interests.

Companies acquired by buyout funds may require significant restructuring, aiming to generate the return targeted by the PE manager, especially if financing the purchase requires large amounts of debt. Therefore, advisors interested in buyout funds may want to take note of each fund manager’s internal value-creation resources and experience.

As with other PE strategies, a general partner (GP) typically negotiates the buyout fund’s transactions and manages investments on behalf of the fund’s limited partners (LPs). A GP usually attempts to construct a fund’s portfolio to include multiple privately held companies. However, the GP may construct a more concentrated or thematic portfolio, focused on companies within specific sectors or geographies, for example, or it may decide to diversify across these dimensions.

Often, buyout funds are further classified by size. Large or mega buyout funds, for instance, can typically make larger purchases in higher-valued companies than small or mid-sized buyout funds and may therefore have a different risk and return profile.6

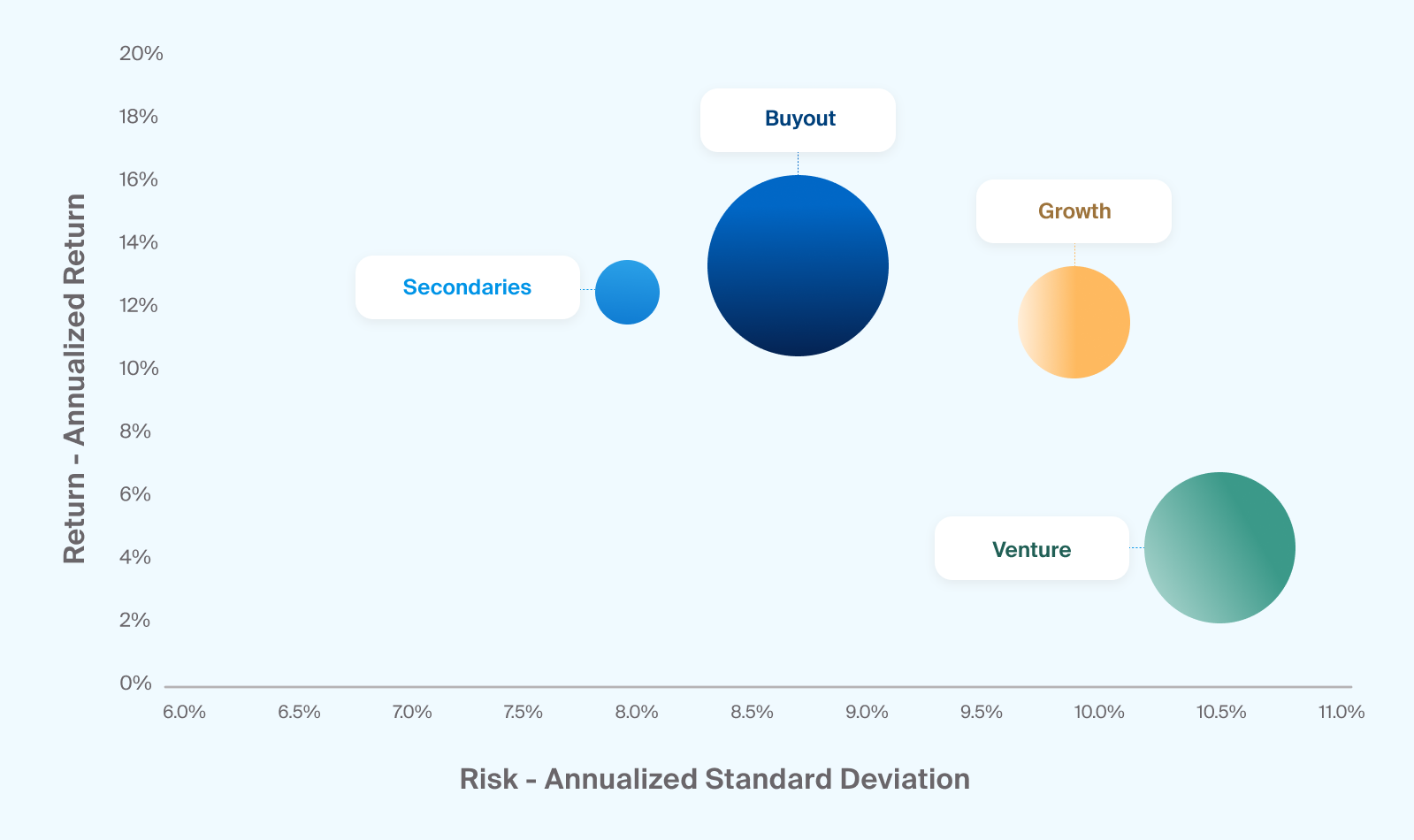

Source: Preqin, return represented by annualized return, risk represented by annualized risk, calculated between 12-2000 and 9-2024, the size of each circle represents the assets under management (AUM) for funds in each category, as of 6-2024

PE buyout strategies represent the largest among PE strategies by capital allocation and tend to differ slightly in risk-return profile (Exhibit 1)

What Are Types of Private Buyout Transactions?

Two main types of buyout transactions include:

Leveraged Buyout (LBO)

A leveraged buyout is an approach more frequently employed by PE firms, in which the firm—or in some cases, a group or consortium of firms—uses a significant amount of debt financing to purchase a controlling or majority stake in a company.7

Management Buyout (MBO)

A management buyout is when the existing management of the company claims, or reclaims, majority ownership of the organization. In many MBO transactions, a PE firm will help the management team finance the purchase, taking a minority stake in exchange for funding.

How Can Value Be Created in Private Equity Buyout Investments?

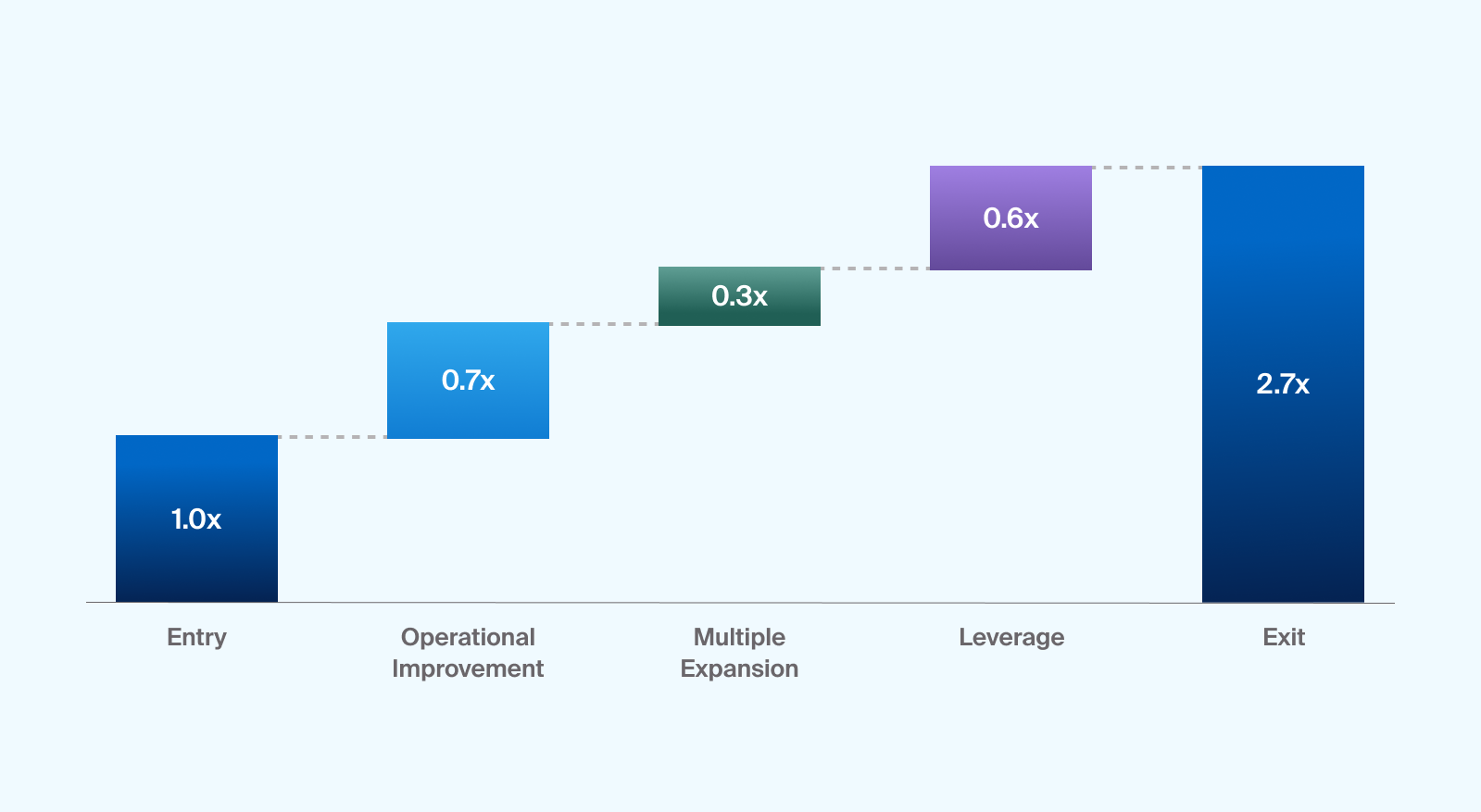

Buyout fund managers, like other PE managers, have a few levers to pull when attempting to create value in their portfolio companies. These levers generally fall within one of three categories: operational improvement, multiple expansion, or leverage. As Exhibit 2 shows, each has contributed to overall value in varying amounts over the last three decades.8

Source: Institute for Private Capital, Data sample includes 2,951 fully-exited deals from 1984 through 2018, with around $945 billion USD in combined equity investments and around $1.9 trillion USD in total enterprise value based on a Stepstone Group proprietary dataset of private transactions. "Pre-2000" is comprised of 272 deals from 1984 to 1999. "2000-2007" is comprised of 1,500 deals from 2000 to 2007. "2008-2018" is comprised of 1,179 deals from 2008-2018. As of January 2022.

A traditional private equity value bridge approach offers a high-level view of how equity investments in portfolio companies have raised value (Exhibit 2)

Operational Improvement

Certain buyout fund managers are particularly skilled at improving the operations of a company to seek to either increase revenues—organically through improved sales, new products, or new markets, for example, or inorganically through acquisitions—or expand margins through cost efficiencies. Buyout managers may focus on specific sectors in which they can offer a competitive advantage through their expertise or network.9

Multiple Expansion

A buyout fund manager may attempt to sell a company a higher multiple than the multiple at entry, or the price the manager pays for each dollar of EBITDA at the purchased company.10 While these multiples can depend significantly on market environments and may be difficult to predict, a manager's ability to source deals and stick to pricing discipline upon exiting an investment can have an influence. In addition, a manager may make operational improvements in strategic parts of the business that may command higher multiples than others.

Leverage

By securing debt financing for an acquisition, a manager can have greater purchasing power, potentially amplifying returns to equity holders. Over time, a buyout fund will typically attempt to pay down the debt used to finance the acquisition, which increases the value of the equity portion by reducing interest payments and increasing the cash flow available. The optimal amount of leverage is dependent on myriad factors, theoretically limited by the degree to which a company’s cash flows can service its debt.11

Risks and Considerations When Investing in Buyout Funds

Manager Selection and Access

Buyout fund returns can be somewhat dependent on the ability of a manager to source potential deals and add value. Advisors and/or their research partners may seek to conduct thorough due diligence when selecting managers, noting each manager’s track record, experience in buyout strategies, and access to deal flow.

Leverage

Using leverage is inherently risky, as the cost of debt has the potential to diminish an investment’s overall return potential.

J-Curve

Drawdown buyout funds tend to follow a pattern called the J-curve, where they will produce negative cash flows in the early years, due to capital calls and management fees paid before there is a chance for the investment to generate returns.12 It may take several years until underlying investments are marked up to their current value or gains realized through exit transactions.

Liquidity and Volatility

Buyout funds tend to be a long-term, illiquid investment because value creation or restructuring can take years to play out, requiring capital to be locked up for long periods of time. Buyout investments tend to be valued only periodically by the owners of the company, which may make them appear less volatile in a portfolio.

Business Risk

All stages of buyout investments come with some level of business risk. For example, the PE firm may fail to restructure the company to add value.

To the extent possible, an advisor should seek to understand the asset manager’s investment philosophy, experience, and the intended exposure of the fund.