What Is Private Equity and How Does It Work?

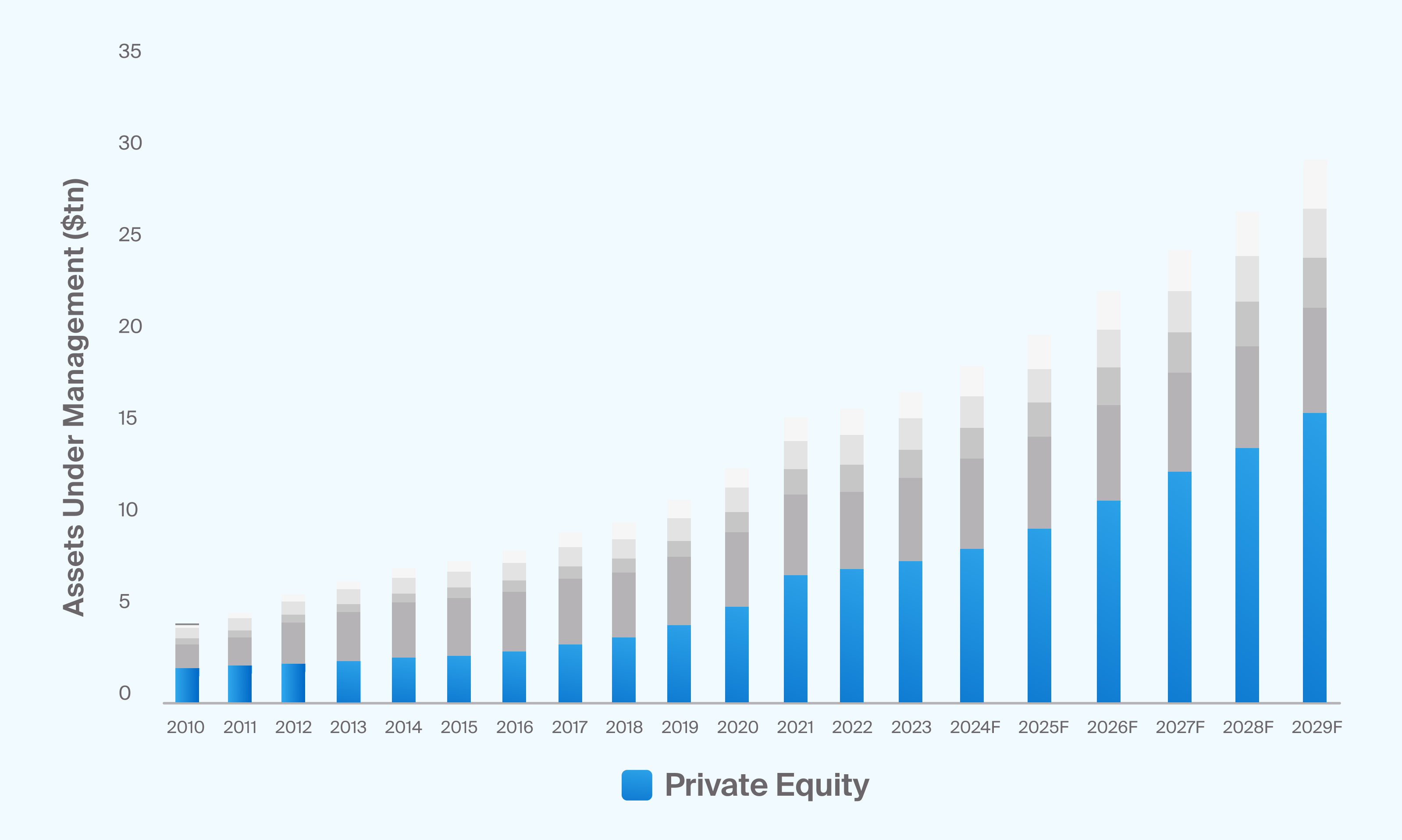

Private equity is the broad term for investing in a privately owned company rather than owning shares in a public company that can be traded on an exchange. Private equity is now the largest alternative asset class: Assets under management reached an estimated $9.6 trillion in 2024 and could reach up to $15.6 trillion by 2029, according to Preqin.1

Source: Preqin Forecasts, as of Q3 2021, 2021 figure is annualized based on data to March, 2022-2026 are Preqin's forecasted figures.

Private equity is the broad term for investing in a privately owned company rather than owning shares in a public company that can be traded on an exchange. Private equity is now the largest alternative asset class: Assets under management reached an estimated $9.6 trillion in 2024 and could reach up to $15.6 trillion by 2029, according to Preqin.

One of the reasons for the growth of private equity is its potential to offer higher returns than both public equities and some other alternative investments over the long term.2 The potential for higher returns comes at the expense of liquidity: unlike public equities and traditional equity investment vehicles, such as mutual funds or ETFs, private equity is not traded on an exchange or offered in a regulated vehicle with daily liquidity. Instead, private equity funds tend to be relatively illiquid because they require investor capital to be locked up for several years to allow time for the investment to increase in value through growth, maturity, or business improvement.

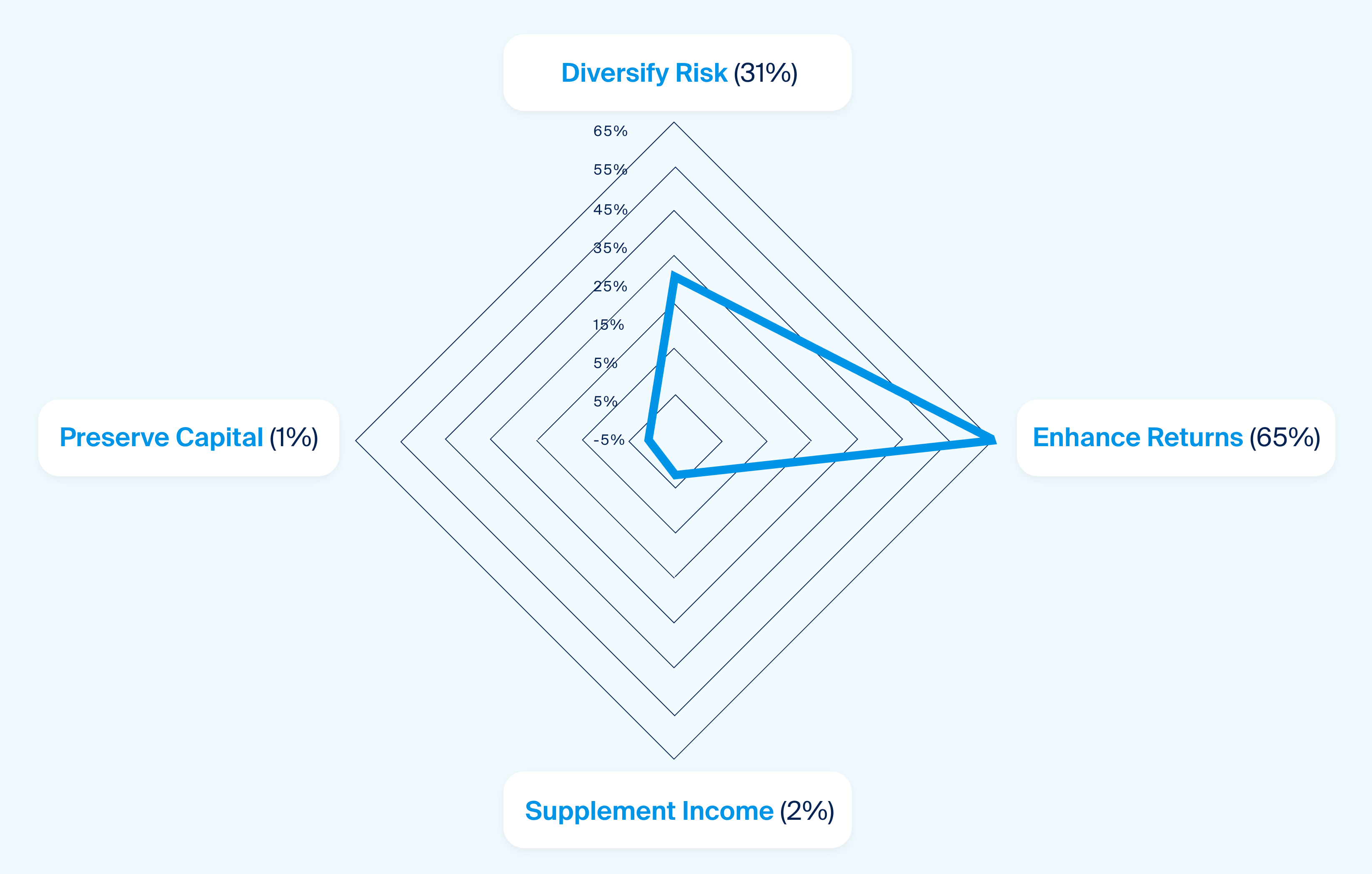

While some advisors may allocate to private equity seeking to improve the return potential of their portfolio, others may be interested in the possibility to diversify traditional equity and bond holdings (Exhibit 2).

Source: CAIS and Mercer, “The State of Alternative Investments in Wealth Management 2023,” December 2023.

While some advisors may allocate to private equity seeking to improve the return potential of their portfolio, others may be interested in the possibility to diversify traditional equity and bond holdings.

While some advisors may allocate to private equity seeking to improve the return potential of their portfolio, others may be interested in the possibility to diversify traditional equity and bond holdings.

Funds structured as a limited partnership, where the asset managers, or general partners (GPs), oversee the investment of the fund’s assets and manage the day-to-day operations of the fund are utilized for many private equity investments. The limited partners (LPs) supply capital and are otherwise passive partners.

The private equity life cycle tends to have three stages, which can sometimes overlap.

Fundraising: Asset managers raise capital for a new fund; LPs commit capital.

Investing: Asset managers deploy capital into new investments; LPs meet capital calls.

Harvesting: Asset managers prepare a mature investment for an exit strategy, such as an initial public offering (IPO) or sale to another company or continuation vehicle; LPs may receive distributions.

Common Types of Private Equity Investments

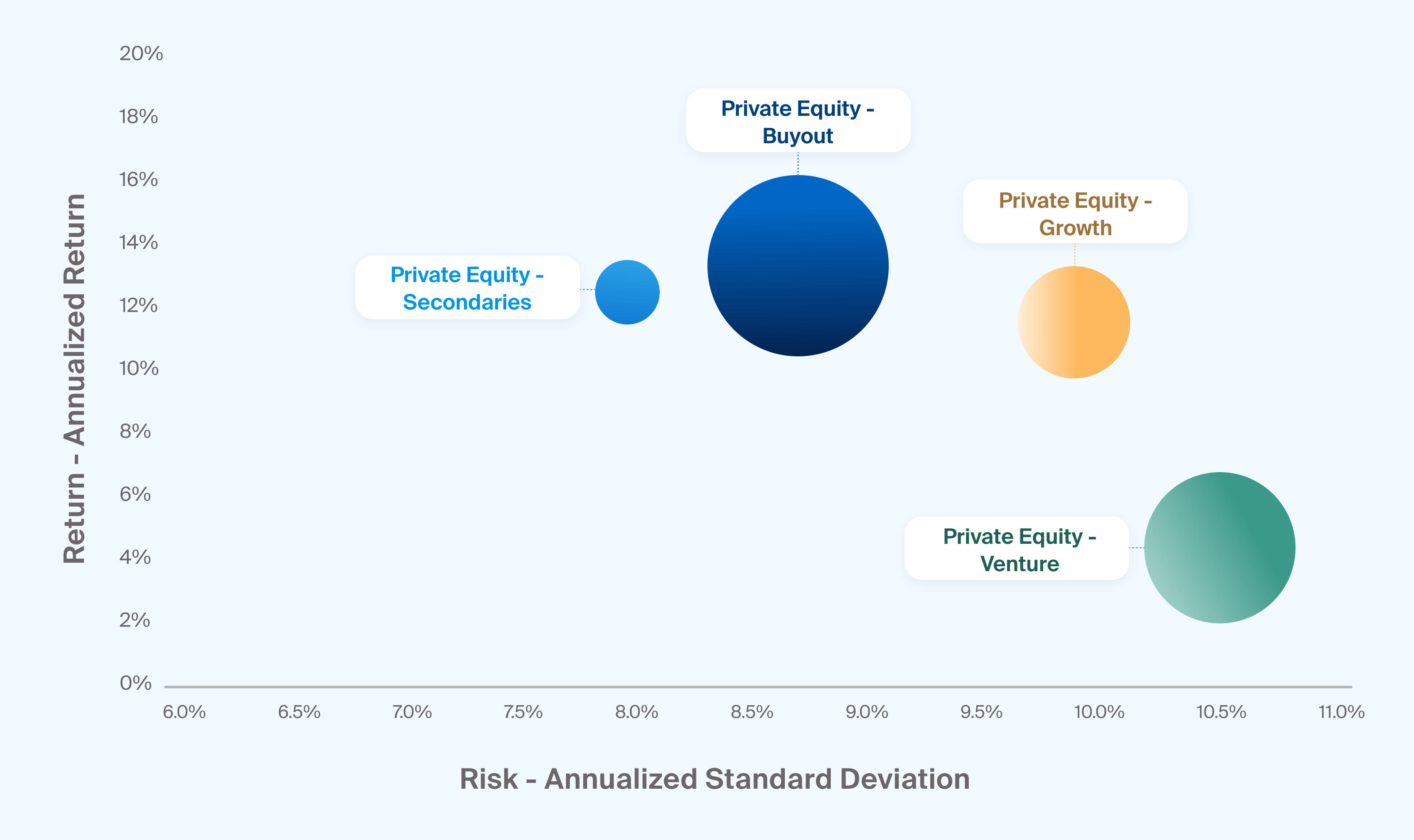

There are a number of categories and sub-categories of private equity strategies, which display a range of risk and return profiles (Exhibit 3).

Buyout is the largest category of private equity. Buyout funds typically seek to gain controlling or majority ownership of an existing private company or a public company that can be taken private, with the goal of creating value by improving the operations of the company. The fund then seeks to sell or take the company public at a higher valuation.

Growth equity investments tend to be in more established businesses than venture capital but may still offer strong potential for growth because typically they are at an earlier stage of development than broader buyout investments.3

Secondary investments consist of the purchase of interest of an existing private equity fund from another investor. They may often be purchased at a discount to the net asset value due to the illiquidity of the investment, though sometimes a premium is warranted.4

Venture capital investments are generally made in new and disruptive companies across industries, such as technology or health care. They may be considered part of the growth equity category. Venture investments are often further categorized as angel, seed, early-stage, late-stage and pre-IPO, with each stage typically offering a different risk and return profile. Venture is considered to be one of the higher risk/return areas within private equity.

Additional Sub-Categories:

Distressed funds typically invest in companies or situations that are financially or operationally challenged and can usually invest across the capital structure. The GP tends to seek operational and financial support to turn the company around through restructuring or other changes. These assets may sometimes be considered a subset of buyout strategies.

Funds of funds seek to combine investments in a variety of private equity funds to diversify private equity exposure by strategy, manager or vintage year.

Infrastructure & energy investments can vary in terms of the risk and return profile, with riskier opportunistic investments as well as lower-risk core-type assets that may have more predictable cash flows and are not dependent on exiting at a higher valuation. These assets can sometimes be categorized as real asset investments.

Source: Preqin, return represented by annualized return, risk represented by annualized risk, calculated between 12-2000 and 9-2024, the size of each circle represents the assets under management (AUM) for funds in each category, as of 6-2024

There are a number of categories and sub-categories of private equity strategies, which display a range of risk and return profiles.

Considerations When Investing in Private Equity

Manager Selection and Access: Private equity returns can be somewhat dependent on access to deals with strong potential and the ability of a manager to add value. This can make due diligence when selecting managers—in terms of their track record, experience and access to deal flow—an important part of the private equity investment process; it also can create significant investor demand for the top-performing managers.

J-Curve: Private equity investments tend to follow a pattern called the J-curve, where they will produce negative cash flows in the early years, due to capital calls and management fees paid before there is a chance for the investment to generate returns.5 It may take several years until underlying investments are marked up to their current value or gains realized through exit transactions.

Liquidity: Private equity tends to be a long-term, relatively illiquid investment because a strategy can take years to play out, requiring capital to be locked up for long periods of time. The asset manager, or GP, controls the investment decisions, and an LP may only be able to exit the partnership in a secondary market that may have limited buyers, if any, or at a discount to the stated value.

Volatility: Private equity investments tend to be valued only periodically by the owners of the company, as opposed to public equity investments which are valued daily or in real time. This can make private equity investments appear less volatile in a portfolio but should not be confused with potential underlying volatility in the real value of the asset.

Business Risk: All stages of private equity investments come with some level of business risk. For example, a business at the venture capital stage may not prove to be viable or competitive; in buyout or distressed transactions the company may not be able to successfully restructure to add value.

Private equity is one of the more established alternative asset classes and appears likely to remain a popular allocation going forward.