A new generation of fully funded, evergreen fund structures is evolving to meet the needs of individual investors who seek exposure to private markets, adding a potentially more accessible alternative to the conventional finite-life, drawdown structure. Yet, each structure introduces its own distinct investment experience and trade-offs.

What You'll Learn

Asset managers are evolving the fund structures they offer to address a broader range of client preferences and accreditation levels.

The flexibility offered by fully funded evergreen vehicles to the investor may come with potential trade-offs, as compared to drawdown finite-life vehicles typical in institutional private markets investing.

A fund structure’s relative liquidity and potential impact on returns should be considered when deciding the appropriate fund structure for a client’s private markets allocation.

Fully funded evergreen fund structures—which include real estate investment trusts (REITs), business development companies (BDCs), interval funds, and registered ‘40 Act funds—are growing in popularity among investor types that were once shut out from accessing private markets.1 Yet, the added accessibility and relative simplicity that many of these structures aim to offer financial advisors and their clients can often constrain asset managers, impacting their return potential.

In this piece, we hope to offer financial advisors a framework for understanding potential fund structure implications for clients interested in private markets. To do so, we compare a broad class of fully funded, evergreen fund structures to drawdown, finite-life structures, the commingled fund structure often associated with private markets investing.

Assessing an Evolving Private Markets Investing Toolkit

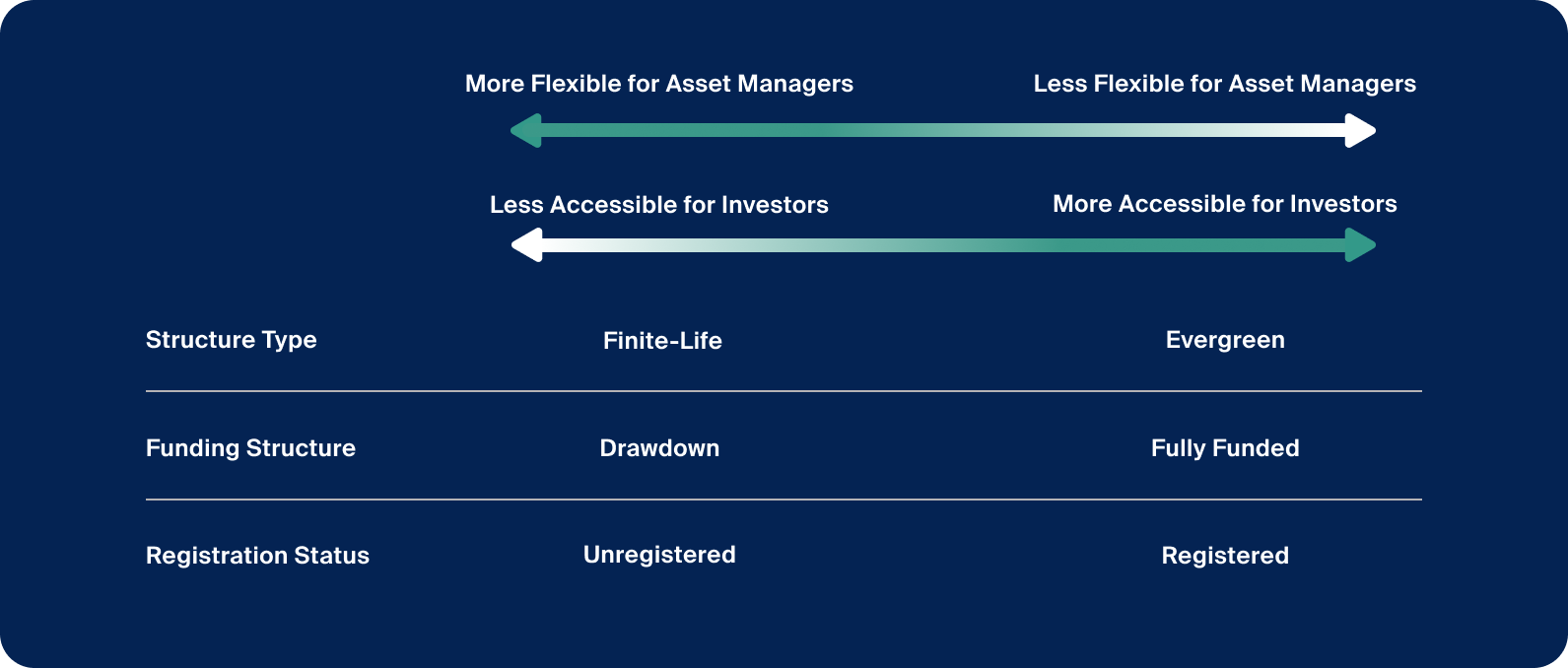

A financial advisor can compare private markets funds across a few structural dimensions, including the funding structure (drawdown or fully funded), the structure type (evergreen or finite life), and the 1933 Securities Act registration status (registered or unregistered) (Exhibit 1).

Funds tend to overlap across these dimensions in various ways, but some configurations are more common than others based on the types of investors they aim to attract. For example, many evergreen fund types tend to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission in line with the ‘33 Act while funds with a finite-life structure tend to be exempt from registration under private placement conditions. Similarly, finite-life funds typically call capital over time through a drawdown mechanism, while investments in evergreen funds tend to be fully funded from the start.

Source: Investment Fund Law Blog, Real Estate Finance Journal, Investopedia.

A financial advisor can compare private markets funds across a few structural dimensions, including the funding structure (drawdown or fully funded), the structure type (evergreen or finite life), and the 1933 Securities Act registration status (registered or unregistered).

Apart from being more accessible to a more diverse set of investors, funds with these newer features (think: evergreen, fully funded, registered) are also associated with potential benefits including investor safeguards, convenient administration, immediate allocation, and enhanced liquidity.2 These structures have evolved over time, in response to the failures of many of their predecessors to attract assets or generate their intended outcomes.3

In private real estate, for example, the non-traded REIT structure first made an appearance in the 1990s but suffered from characteristics that ultimately hampered its adoption—such as high upfront commissions, onerous fee structures, unclear valuations, arbitrary fixed-price offering windows, restrictive limitations on liquidity, and a finite life of seven to 10 years, at which point an exit would typically be initiated.4

By contrast, today’s REITs have been designed to be more investor friendly.5 For instance, they are typically structured with a more liquid sleeve in the underlying portfolio to provide enhanced opportunities for redemptions, a feature that the older generation of non-traded REITs was criticized for lacking. Asset managers have also since introduced improvements including the perpetual structure, lower fee loads relative to the older generation, and more frequent and transparent valuations.6 Such enhancements have appeared to enable a rebirth of sorts, repositioning the non-trade REIT structure as a more viable way to access institutional-quality real estate.7

BDCs, a vehicle used to access private credit, have similarly evolved since their creation in the 1980s. The perpetual non-traded BDC structure, in particular, has become more popular in recent years due in part to improvements over the older generation of fixed-life private BDCs, such as new liquidity features, continuous periodic capital raises, and commitments to avoid liquidity events.8 Management fees are also typically charged on net assets rather than gross assets,9 the latter used to determine fees for legacy publicly traded and fixed-life BDCs. As such, they may offer investors a relatively more efficient vehicle to access private credit assets with longer investment horizons.10

Last year, in a survey we conducted with Mercer, more than 45% of asset managers told us that they planned to roll out new investment structures,11 potentially allowing them to market their strategies to a wider range of investors. If these newer structures continue to gain momentum, it may be important for financial advisors to understand and be able to discuss the potential implications of their added investor flexibility.

Defining Structure Type and Funding Structure

As mentioned before, we focus here on comparing fully funded, evergreen fund structures to drawdown, finite-life structures, which have been the most prominent vehicles historically in private markets investment.12

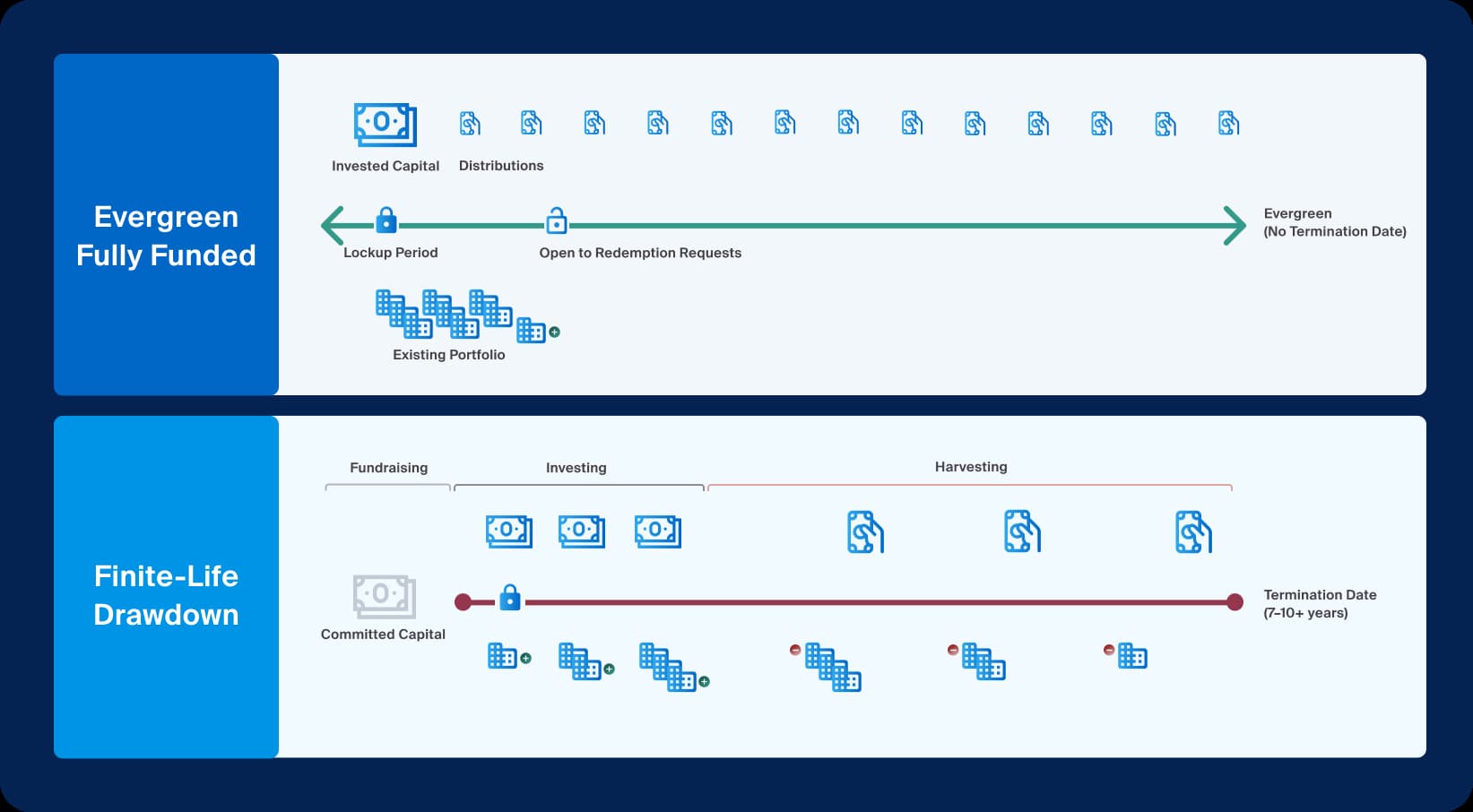

Evergreen fund structures, also known as perpetual or perpetual-life, are typically open to new investments and redemptions,13 with some limitations, and have no specified termination date. By contrast, funds with a finite-life structure will not accept new commitments into the fund beyond the initial fundraising period or allow investors to redeem their capital from that fund for the rest of its life,14 which has a predetermined termination date. You may also hear people in the industry refer to these same structures as open-end (open-ended) or closed-end (closed-ended); however, these terms may also connote different meanings.

Fully funded and drawdown both refer to the nature by which capital is collected and employed by the asset manager. Investments that are fully funded require an investor to transfer the entire intended commitment to a fund’s asset manager upfront, all at once. For a mature, fully funded, evergreen fund, the capital invested typically provides immediate exposure to a portfolio of assets. Structured in this way, the asset manager often makes distributions at a regular cadence throughout the fund life, based on the income generated from the portfolio assets.15

With a drawdown funding structure, the asset manager calls some or all capital committed over a multi-year investment period and can use that funding to acquire assets for the portfolio. By the end of the fund life, the manager will generally aim to have sold the assets from the portfolio and distributed the proceeds to its investors.

These differences can have significant, and sometimes less obvious, implications that advisors should consider. To simplify our comparison later in this article, when we refer to evergreen funds or structures, we are referring to those that are also fully funded; similarly, when we refer to finite-life funds or structures, we are referring to those that also have a drawdown funding structure.

Footnotes

For illustrative purposes only.

Advisors considering private market assets allocations will find that differences between fund structures may impact their clients’ investing experience.

Matching Fund Structure With Liquidity Needs

Liquidity is a first-order consideration. Under ordinary circumstances and not considering the secondary market, limited partners (LPs) of finite-life funds typically have no mechanism to proactively redeem their interests during the life of the commingled fund.16 Meanwhile, evergreen funds typically offer some liquidity—with important limitations.

Investors in evergreen funds can submit requests for redemptions during predetermined windows, which are typically quarterly. The specific mechanism for redemption and frequency depend on the specific fund.17 A manager’s obligation to meet those redemptions and the frequency of the redemption opportunities depend on the registration status of the fund and that specific fund’s terms.

Evergreen funds investing in private market assets can have features that restrict redemptions like initial lockup periods, early redemption fees, fund-level redemption limits, and the option of completely suspending redemptions. These features typically help manage the liquidity mismatch between the evergreen fund structure and its illiquid underlying assets. Each mechanism can be used in the interest of protecting the fund and its existing investors from the detrimental effects of outsized redemptions that would lead to a forced sale of assets.

As such, it is more appropriate to label these funds as “semi-liquid” and for advisors to consider these potential limitations when assessing the suitability of and/or appropriate allocation to an evergreen fund that invests in private assets.

Understanding a Proration Event

Evergreen funds with fund-level redemption limits may be subject to proration events, in which redemption requests in aggregate, and at any point, exceed the fund-level limit set by the asset manager. In this situation, investors would only receive a portion of their redemption request. Take, for example, a situation where investors in a fund with a 5% fund-level quarterly limit collectively request to redeem 20% of NAV. In this example, each investor would receive 25% of their requested amount.

Findings suggest that, collectively, proration has been a low-probability event.18 As such, for most funds and during most periods, investors can get all their money out in any given quarter.19 However, instances in which proration occur, which tend to increase in periods of market distress, may result in limited liquidity.20

Again, finite-life funds do not allow LPs to redeem during the life of the fund, and cash flows to and from investors are determined by the general partner (GP). But, by definition, these fund structures have a finite life, and as such, LPs can plan for ultimate cash distributions, the pattern of which relates to the asset class, strategy, manager, and fund.

Understanding How Structures May Impact a Fund’s Return

In addition to affecting liquidity, these fund structures may also impact an investor’s ultimate return—often in less obvious ways that we highlight in this section.

Liquidity Sleeves

Offering liquidity can come at a cost to all investors in an evergreen fund. To meet potential redemption requests, managers must deal with the liquidity mismatch between the fund structure and the inherently illiquid underlying assets like private real estate, direct loans, and private equity. Liquidity sleeves are a potential solution, in which asset managers hold a portion of the capital in liquid cash equivalents and/or access a line of credit.21 While potentially helpful in some cases, this liquidity sleeve can also introduce a drag on ultimate performance or, at minimum, a deviation from the primary investment objective of the fund.

Manager Control

Evergreen structures may allow managers to continuously solicit additional capital.22 Yet, they trade-off control of fund inflows and outflows. With less control, they may be pressured to deploy new capital (or otherwise hold cash, dragging down returns) at inopportune times. In other scenarios when their liquidity sources are insufficient to meet redemptions, they may have to sell assets, potentially to the detriment of existing investors. Proration, or in more extreme cases, gating, can temporarily sacrifice an evergreen fund’s liquidity advantage to protect existing investors, but these situations can also damage a fund’s reputation and may tarnish its ability to attract new capital.23

By contrast, managers of finite-life structures do not have to maintain liquidity in the same way and thus have greater flexibility in timing their capital calls and exiting their portfolio assets. As such, they’re able to focus the fund’s entire capital base on their primary investment mandate.24 Their finite life, however, presents some potential challenges compared to an evergreen vehicle.

For instance, if they can meet redemption requests, evergreen structures may have the advantage of waiting to sell assets, compared to finite-life structures, which may be subject to an unattractive exit environment like an economic downturn. Nevertheless, investors may be able to mitigate the inherent timing risk of investing through finite-life fund structures by diversifying through a vintage diversification program.

Cash Drags

As briefly mentioned above, fully funded, evergreen funds that invest in drawdown, finite-life funds through a fund-of-funds model may face additional challenges that result in cash drag. Given the manager must manage commitments and redemptions as an investor directly investing in a drawdown, finite-life fund would, they may have to hold incoming cash for a prolonged period, which may hinder fund performance.25

Similarly, an evergreen fund investing directly in private market assets may not be able to deploy new cash inflows fast enough to avoid cash drag given private market investments may take weeks or months to identify and acquire. This issue may be more pronounced as a fund scales and new cash becomes a larger part of the total portfolio.

Valuation Uncertainty

Finite-life fund structures can mitigate valuation uncertainty when it matters most for the investor—first, when they invest, and later, when they receive their distributions. Ultimately, in these structures, the manager distributes capital based on the market prices of the fund’s underlying transactions. Cash deployed into a finite-life fund does not typically expose an investor to a portfolio of legacy assets, which may be advantageous or disadvantageous in different phases of a market cycle.

Evergreen funds, on the other hand, are constantly raising capital. As they onboard new investors and redeem others, they typically do so based on book values and not transaction-based prices. If the net asset values (NAVs) are inaccurate, investors risk paying too much or not getting a fair share upon investment or redemption.26 Private asset valuations tend to lag public markets valuations, so again, this feature may be advantageous or disadvantageous in different phases of a market cycle.

Taking a Longer-Term View Across All Structures

Fund structures introduce meaningful trade-offs for advisors seeking to customize portfolios to suit their clients’ unique goals and constraints. For advisors with clients for whom illiquidity is less of a concern and their accreditation permits, forgoing the flexibility of an evergreen structure and aiming to maximize total return through a finite-life fund structure may be more desirable. This finite-life structure may be particularly well aligned for investment strategies that aim to generate most of their returns from capital appreciation. In our next piece, we plan to dive into these considerations further.

The nature of the underlying private assets means that regardless of structure, private market investing may be better suited to a long-term approach to investing as opposed to short-term trading. As with any private market investment, advisors should be aware of the risks, which may include illiquidity, loss of capital, use of leverage, and other market or business risks, depending on the strategy.